When I got my first job in banking, I soon realized that I had entered a world full of rules. Our hometown bank had a small lunchroom with unremarkable tables and stacking chairs scattered about. I was pinching pennies, so the this quickly became the place to eat my sack lunch. Next to the lunchroom was a fancy breakroom set up more like a living room, with comfy sofas, chairs, and coffee tables. I learned the rules of the two rooms very quickly: Only the officers of the bank could use the breakroom; the lunchroom was reserved for people like me. (I silently dedicated myself to earning the right to join those in the breakroom, but that’s a story for another day.)

One day they asked me to help inventory the cash in the vault. This task was full of rules, some more obvious than others. The first rule: take no cash. Well, duh! They had to tell me, because evidently that rule had been broken by long gone cash counters who failed to see the obvious. (I’m guessing they were in jail?) A second rule: all piles of cash must be counted twice with the same result. (This was before the automatic cash counting machines.) Another rule: all the bills must be facing the same direction. So many rules!

All the spoken rules paled in comparison to the unspoken rules. For example, there was a written dress code: Men must wear suits, women must wear dresses. But within those spoken rules were the unspoken rules: Men should never, ever wear a brown suit. And woman must always, always wear panty hose. In meetings, there was no assigned seating, at least in writing. But we all knew who would sit at the head of the table, who sat close to head of the table and who sat in the chairs along the walls or in the back of the room. Hint: the lunchroom people sat along the wall; the fancy breakroom people sat at the table.

The unspoken rules really showed themselves when it was time to speak up in the meeting. Disagreements were allowed – but only by certain people and only to a point. We were managing risk in two fronts. The first was in protecting the bank’s assets. The second was in protecting our own careers. As a result, most decisions were made by a select few, with little to no real feedback from those closest to the action.

Being in a world full of rules was great for me because following rules was one of my specialties. I had learned early in life to figure out what the parents wanted, how the teachers graded and what the friends rewarded. I operated with just enough rebellion to be seen as my own person. With that set of patterns, my career would flourish.

That mindset might help me have a solid banking career. But with that mindset, I would never change the world.

This week, I watched the movie Air, A Story of Greatness. It’s the story of Nike courting Michael Jordan in the early 80’s, before he was MICHAEL JORDAN and when none of us had ever heard of Air Jordans. The opening scenes brought back the hallmarks of the early 80’s, from the music (“I want my MTV”), to Ronald Reagan and Mary Lou Retton, from “where’s the beef” to Cabbage Patch dolls and the Rubiks’ Cube. These scenes took me back to the days when I was a young banker, learning all the rules of how to get along in the corporate world.

As is almost always the case when looking back on something that became huge, the movie shows us how it almost didn’t happen. The storyline takes us through the many ways Sonny Vaccaro - the Nike talent scout that recruited basketball players for the brand - broke the rules to bring his wild idea to life. His direct boss hated the idea. The CEO Phil Knight forbid him to take it further. Jordan’s agent threatened him in some very colorful ways. But the movie shows Vaccaro standing firm in his own instincts. He saw something in the way Jordan made his historic shot playing for the Tarheels that portended future greatness. It’s hard to remember that at one time, Michael Jordan was just one of thousands of 18-year college players who dreamed of being great NBA players. Following his gut feeling, Vaccaro took extraordinary risk to sign Jordan, going against the rules at every point. We all know how the story ends. According to the epilogue in the movie, Phil Knight anticipated $3 Million in sales of Air Jordans. Instead, they sold $162 Million. In one year.

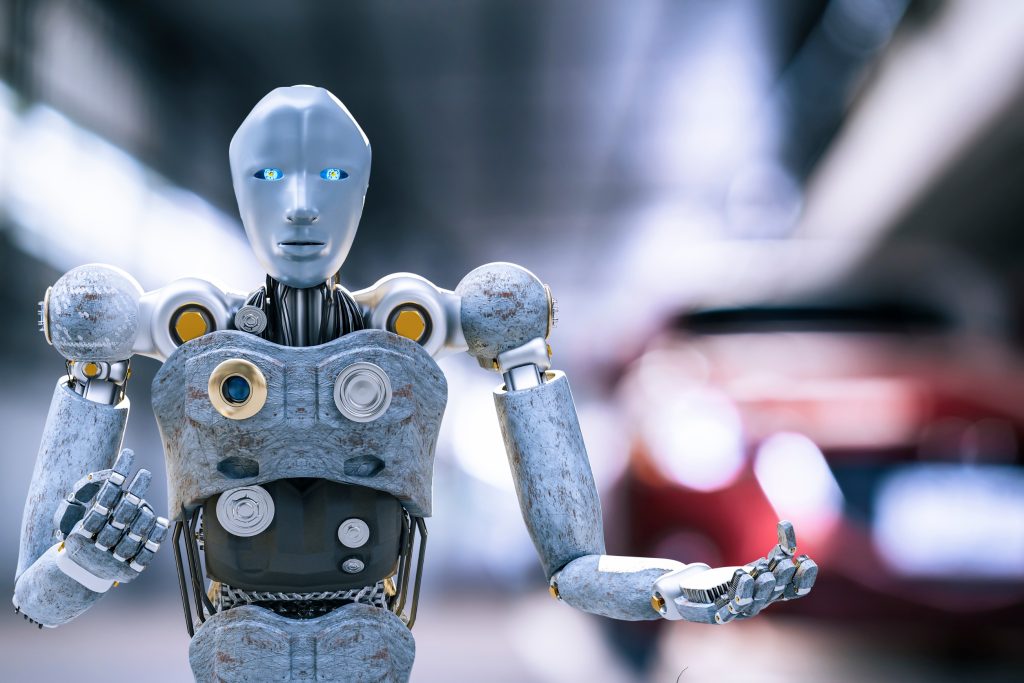

What made Vaccaro break the rules, and people like me follow the rules? In my book Dancing the Tightrope, I reflect on the difference between our Rules and our Tools. I liken the Rules to being a robot here:

Our unconscious patterns run us, just as surely as if we were robots running on the programming code of their inventor. Learning to operate creatively and consciously requires MUCH MORE than a simple decision to change. Why? Because emotions lock the original programming into place. Until we access those emotions and then “rewrite” the program, we cannot change the pattern.

While my body was running down the hill on Mocha, the robot was running my mind. If I were ever to ride again, it seemed wise to do something about the robot. In other words, it was not a skill problem. It was a mindset problem.

The inner robot isn’t a horrible thing. It’s a beautiful form of self-protection. However, the inner robot isn’t designed to take chances and do great things. It’s designed to go along to get along. If we aspire to do something great, we need to do the personal work to loosen the grip of our rules and patterns. Yet, there is also a catch on this path. In teaching hundreds of self-awareness sessions, I’ve learned that it’s dangerous to strip us of our Rules without providing solid access to our inner Tools. We must hone our Tools, such as listening, noticing, patience, courage, curiosity and feel.

In the movie (and I’m guessing in real life), Sonny Vaccaro followed his gut feeling about Jordan. In watching the tape, he noticed Jordan’s hunger to take the shot under pressure. When he hit obstacles, he sought advice and knew when to listen and when to courageously break the rules. He patiently (and sometimes impatiently) stayed with his idea until those above him came around. He also seemed more committed to doing the job they hired him to do than in preserving his seat at the table.

I wonder how many great ideas never got past the first obstacle because a rule follower didn’t dare go any further.

What inner Tools do you draw on when the chips are down? How well do you access both your head and your heart when making decisions? How well do you distinguish between a true gut feeling and wishful thinking? Where can you challenge your rules and patterns to take the chances you’ve always wanted to take?